Headrest’s History

“Headrest – 50 Years of Compassionate Care for Neighbors in Crisis.”

Jason was lucky. He had been struggling with a substance use disorder for years. He lost his license in 2017, then lost his job, and faced a dark future. Jason’s luck changed when he entered Headrest’s residential treatment and a counselor referred him to Headrest’s Opportunities for Work program. Jason worked with H.O.W.’s director, Lori Bartlett, to learn interview skills, craft a résumé, and even get some new clothes to add a touch of professionalism. The job coaching paid off. “I have an amazing job with Hypertherm,” he said. And, in turn, that stability has allowed Jason to regain his driver’s license, own a car for the first time since 2017, and own a home – “not an apartment” – with his fiancée for the first time in their lives.

Jason’s advice for those who struggled as he did?

“The phone is not heavy. Pick up the phone to call Headrest,” he advised. “You’ve got let someone you know you need help to get help.”

That’s solid advice, particularly since Headrest has answered calls from Jason and thousands of others for the past 50 years.

Headrest’s Hotline – 1-603-448-4400 and the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 1-800-273-8255 – are often the first lines of defense in times of personal crisis. It’s been that way, every hour, every day since 1971. Headrest has answered the call for an astonishing unbroken streak of over 440,000 hours.

Where did this dedication and commitment to community service come from?

COUNTERCULTURE COMING …

Hill Anderson, Dartmouth ’70, spoke of that in his Brief History. “In the summer of 1970, I constructed a proposal for a hotline and referral service for both the Dartmouth community and the general public.” Rev. Paul Rahmeier, chaplain at Dartmouth’s Tucker Foundation, liked Anderson’s proposal and made sure the group had office space in the basement of College Hall.

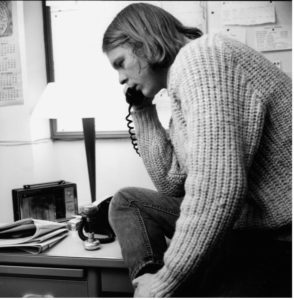

Hill Anderson, 1971 (photo courtesy of the VALLEY NEWS)

Hill Anderson, 1971 (photo courtesy of the VALLEY NEWS)

Dartmouth President John Kemeny even donated the use of his summer cabin in Lyme. “His cabin became the group’s ‘summer hostel,” said Ford Daley, Dartmouth ’61, a teacher at Hanover High School and early Headrest advocate. Kemeny’s cabin was a welcome spot for Headrest volunteers to unwind and learn some back-to-the-land skills like digging a well, gardening, and communal living.

Anderson and others had been inspired by the Woodstock Music Festival where the Hog Farm commune provided a free kitchen, drug counseling, and security dubbed the Please Force for festival goers.

“As with other centers sprouting up across the country, HEADREST took its idea from the Hog Farm,” Anderson wrote. “A place where our ‘brothers and sisters’ in the counterculture who were experimenting with drugs could find a friendly ally to ‘talk them down,’ as opposed to being confronted by a disapproving emergency room physician with a hypodermic needle full of Thorazine, possibly accompanied by an officer.”

Anderson realized the hotline volunteers needed support and advice from mental health professionals and turned to Dartmouth’s Department of Psychiatry, where he conferred with Dr. Peter Whybrow. In short order he recruited Dr. Whybrow’s administrative assistant, Dereka Smith, as Headrest’s first volunteer. Soon Dereka’s sister, Tamar, signed up along with college friend Mitch Wallerstein and many others on campus and in the community.

During a field trip in late 1970 to visit a planned hotline at UNH, Hill and the Smith sisters discussed their plans on the ride back to Hanover. “I remember leaning back on the car seat’s headrest,” recalled Tamar Smith, “and thinking – Headrest! – that’s it. That’s our name.”

So, with a new name, a growing list of volunteers, and space in the basement of Dartmouth’s College Hall, Headrest was ready to take its first call in January 1971.

Mitch Wallerstein, Dartmouth ’71, remembered “vividly, the worry that people would come up from New York or Boston, get in trouble with drugs, have bad trips, and the Upper Valley was ill equipped and unprepared to deal with these issues.” To prepare for problems, “we set up a training regime” for hotline volunteers, “and took it very seriously. We had to be sure we knew what we were doing.”

Alex Henzel staffed an outpost in Lebanon for the NH Bureau of Drug and Alcohol Services. “Donlon Wade approached me and Elizabeth Gay (now deceased), since we were both social workers. We attended training sessions and retreats where we could discuss the insights volunteers had gained… Calls came from throughout the community and some could be serious crisis calls.”

After graduating from Dartmouth, Wallerstein went on to earn a master’s degree in public administration and then returned to Dartmouth a year later, just in time to administer a grant designed to spur community development projects. One of the non-profit recipients was Headrest, which had relocated to Lebanon.

… COMING TO LEBANON

By 1972, Headrest had found its new home on Bank Street in Lebanon. “The genius of Donlon was that he recognized that not everyone was comfortable visiting the Dartmouth campus,” said Ford Daley, who had encouraged Hanover High School students to volunteer at Headrest, “so moving to Lebanon made a lot of sense.”

FRONT ROW, seated: (Name Not Available), Julie Hawthorne, Chris Nord, Donlon Wade, Deborah Jones.

SECOND ROW, seated: Karla Bock, NNA, Chris Nord, Helen MacLam, Valerie Mullen, Audrey Westhead.

THIRD ROW, seated: Bill Bond, NNA, Phil Sharp, Gail Charpentier, NNA.

BACK ROW, standing: David Ralston, Alan Altman, Rich Balagur, NNA

Headrest archive

Although Headrest had to move seven times in seven years – always looking for better space or cheaper rent – it stayed in Lebanon, where its impact on the community and its reputation for 24/7 hotline help became well known. In addition to a core of volunteers, Headrest had four full-time employees – each earning $30 a week. Throughout those years, one thing was constant: Headrest was always struggling to make ends meet.

“I remember most how many people we helped by active listening on the hotline or drop-in,” wrote Julie Hawthorne, at the time a new graduate of Hanover High School. “Active listening techniques worked like a charm: once folks felt that others truly listened, they were usually able to deal with their crisis at hand.

“I was also fond of the fact we helped each other get better at what we did. I admired my friend Gail Charpentier, as she was one of the talented grant writers. I admired Donlon Wade; he had the ability to make things happen.

“Many, many people were helped, and I was serious about what I did, although I remained a volunteer for about three years. It gave me the confidence to later get my MSW and LCSW, after migrating to California to secure a college education.

“It was an intense adventure.” Hawthorne concluded.

HEADREST FINDS ITS HOME…

One name that keeps reappearing in everyone’s recollections of “early Headrest” is Donlon Wade. Donlon, who quit a construction job in 1971 and, as Hill Anderson remembers, “took over when I left and has been the main consistent force behind Headrest for years since.” Like many early Headresters, Wade had benefitted from the counsel of Elizabeth Gay and Jeff Title, a psychologist, “who gave me ten years of free supervision as well as being a long-term board member,” he recalled. Wade helped Headrest develop new services: counseling programs, free support group meetings, emergency housing, and, perhaps most memorable, finding a permanent home for Headrest. Wade’s father, a realtor, discovered an affordable, Cape-style house sitting on a postage-stamp lot directly behind the Lebanon Fire Station.

“14 Church” – Headrest’s street address – had its first open house on Dec. 8, 1978. Not only could it house the Headrest hotline, administrative and counseling offices, but also two bedrooms for emergency overnight lodging.

Valley News clipping, Dec. 6, 1978

FUNDING, FUNDING, FUNDING

With its new home came new expenses for supplies, equipment and mortgage payments. In early 1980, wages for workers on the 24/7 hotline were $3.50 an hour and the staffer who took the graveyard shift (10:30 pm to 8:30 am the next day) earned a dismal $10. More ominous, Headrest had lost its share of Title XX federal funds. Grafton County’s commissioners voted against a compensating amount for Headrest, and Lebanon’s City Council voted to allocate only $1,666 of the agency’s $7,000 request. Luckily, a Washington, D.C.-based foundation came to Headrest’s rescue with a $10,000 grant.

Jim Rubens, a Hanover entrepreneur and early Headrest volunteer, recalled being recruited by Wade to help bring Headrest back to financial solvency. “I guess my most significant contribution was my time as board president during the ‘80s when Headrest needed to get its books in order,” he said. “We needed Headrest to be in good graces with United Way and state agencies involved in funding and certification.”

By 1981, Headrest had developed a program for emergency overnight lodging for people brought in by local police for public intoxication or drug use. “I’m kind of enthusiastic with the program,” Peter Giese, Enfield police chief, told the Valley News on June 20, 1981. “Certainly, I’m going to use it when then occasion arises.”

Once a client arrived, EMT volunteers would evaluate the person to see if she or he needed medical attention or could stay, supervised, overnight at Headrest. In the morning, staffers offered advice about support groups like Alcoholics Anonymous. Headrest was the first of six statewide centers to open. In later years, EMTs from the Lebanon Fire Department provided medical clearance for incoming clients.

Headrest soldiered on through the ‘80s and ‘90s, still answering the hotline every hour, every day, running free substance use disorder workshops, and keeping beds open for emergency overnight needs. Wade and other staffers made sure Headrest appeared on town warrant articles to appeal for annual funding. “I had to give our spiel every year to nine towns – Lebanon, Plainfield, Hanover, Lyme, Enfield, Canaan, Grafton, Thetford, and Hartford – but we were successful each year because we could explain the need for our services in each town,” Wade added.

Gina Capossela, a staffer from 1988 to 2001, started as a hotline trainer and coordinator, an important role, since most hours of the 24/7 hotline were covered by volunteers. For her, Headrest “was not a sterile workplace. Real people worked there, made friends, fell in and out of love. I grew up there. What I learned at Headrest I’ve used for the past 35 years. My gratitude for Headrest is as deep as it vast.”

GINA CAPOSSELA (photo courtesy of the VALLEY NEWS – Geoff Hansen)

GINA CAPOSSELA (photo courtesy of the VALLEY NEWS – Geoff Hansen)

Capossela’s colleague, Greg Norman, started his career in community health services when he signed up with Headrest. “I practice every day the listening skills I learned at Headrest,” he said.

He had a lot of time to practice, starting in 1995, when four students from Mascoma High School visited Headrest and “told us that the hotline was great, but we need to have a line staffed by teenagers who can talk about teenager issues.” With that suggestion, David Sandberg, Gina, and Greg developed a training program for teen volunteers, which led to a Headrest initiative – “H.O.P.E.S.” – for Headrest Outreach Program for Educators and Students.

“We took that on the road to schools like Woodstock High, Thetford Academy, and Mascoma High and Indian River Schools.” Norman said. “We didn’t get many calls on the Teenline, but school discussions were an interesting mix,” often centered on topics like substance use, harmful personal relations, and suicide prevention. Eventually that led to a close connection with the NH Teen Institute, thanks to Rowan Wade who volunteered as a Hanover High student and later became a project coordinator for the Teen Institute.

GREG NORMAN (Headrest archive)

GREG NORMAN (Headrest archive)

By 1996, Headrest could look back with pride at 25 years of community service. Ron Michaud, Headrest’s executive director at the time, recalled a successful anniversary celebration, which featured a benefit concert by renowned pianist, Peter Serkin, hosted by Dartmouth College at Spaulding Auditorium. “It was really something,” he said. “We raised over $37,000 that night, but it wouldn’t have been possible without the help of Bathsheba Freedman, who served on our Board, and her husband who, fortunately for us, was the president of Dartmouth College.”

The 25-year mark also marked the growing professionalism of the organization. Michaud recounted that the Hotline earned accreditation from the American Association of Suicidology. Hotline staffers switched from volunteers to paid workers, many with master’s degrees. Headrest counselors were encouraged to earn graduate degrees or become Licensed Drug and Alcohol Counselors.

The physical plant got an upgrade, too, including more space for residential quarters, a conference room, a small and very needed kitchen, and updated phone lines. By 1999, Headrest offered 10 beds for clients who needed safe, supervised, sober housing as they waited for a place in longer-term programs in Manchester or Bethlehem, NH.

Renovation party in 1990s: John Vansant, architect and board member; Mary Lou Bryant and Sukie Grover, Out of the Woodworks crew; David Shumway, executive director)

Renovation party in 1990s: John Vansant, architect and board member; Mary Lou Bryant and Sukie Grover, Out of the Woodworks crew; David Shumway, executive director)

In the midst of these service improvements, one thing stayed the same – the implacable need to raise money to stay afloat. Headrest was able to pay the bills through a combination of NH Health and Human Service block grants, foundation support, private donations, United way contributions, and community fund-raisers. But each new fiscal year seemed more challenging than the last.

When Mike Cryans, a Hanover banker and Grafton County Commissioner, took over as executive director in 2003, he had to tell staff “We do wonderful things, but if we don’t run Headrest as a business, we won’t be around to do more wonderful things.” Once a strategic planning consultant asked Cryans for his top three priorities for Headrest. That was easy: “funding, funding, funding.”

OPIOIDS, SUDDENLY

By 2014, calls and caseload had taken a distressing turn. Although alcohol-related cases remained a common challenge, more clients were coming to Headrest for a supportive place to recover from opioid use. Four years later, opioids like heroin and fentanyl led to a disastrous rise in addiction and death throughout New England. New Hampshire had scrambled to set up its “Hub and Spoke” system called The Doorway-N.H., which was meant to provide quick assistance for people looking to get help.

Laurie Harding, Headrest’s past board chair who served on Headrest’s board for 15 years, could see what was in store for Headrest. “I was alarmed by the growing number of substance use disorder cases,” she recalled, “in the Upper Valley there didn’t seem to be any services dealing with these issues except Headrest. I thought ‘How can we make a difference?’”

She credits Cameron Ford, Headrest’s current executive director, with helping to make such a difference. “Over the years we (Cameron, staff, and Board) have gotten better at articulating a vision of the future which includes a continuum of care,” Harding said. “We had an excellent residential program for years, but what happens to clients when their 90 days of support are up? That’s why our outpatient counseling, plus job placement and coaching for good jobs, are essential parts of our continuum of care.”

Recovery Friendly Workplace inauguration in NH, 2018: second from left, Cameron Ford, Headrest executive director; Governor Chris Sununu; Laurie Harding, Headrest board chair; Stacey Chiocchio, Hypertherm; Matt McKenney, Hypertherm and Headrest vice-chair)

Recovery Friendly Workplace inauguration in NH, 2018: second from left, Cameron Ford, Headrest executive director; Governor Chris Sununu; Laurie Harding, Headrest board chair; Stacey Chiocchio, Hypertherm; Matt McKenney, Hypertherm and Headrest vice-chair)

In February 2018, Headrest leased office space from Alice Peck Day Hospital at 141 Mascoma Street, Lebanon. This became the headquarters for out-patient counseling, DUI school, administrative offices, and — in pre-Covid times — meeting space for support groups. Physicians at APD supervised Headrest’s medically assisted treatment program. Equally important, moving to the APD campus opened up space for residential needs at 14 Church, which now has 14 beds to accommodate the expected increase in clients with substance use disorders.

HAPPY 50th BIRTHDAY, HEADREST!

Turning 50 gives Headrest a chance to take stock of itself since starting in the basement of Dartmouth’s College Hall. NH Governor Sununu’s proclamation celebrating Headrest’s 50th is a good inventory of its accomplishments.

Thousands of residents in the Upper Valley and beyond have been helped in 2020 thanks to services provided by Headrest!